Sydney researchers are warning swimmers to remove contact lenses before entering the water to avoid the risk of infection, after identifying Acanthamoeba in seawater at four NSW coastal sites.

The new research, published in Science of The Total Environment, is a collaboration between UNSW Sydney, University of Technology Sydney (UTS) and the University of the West of Scotland.

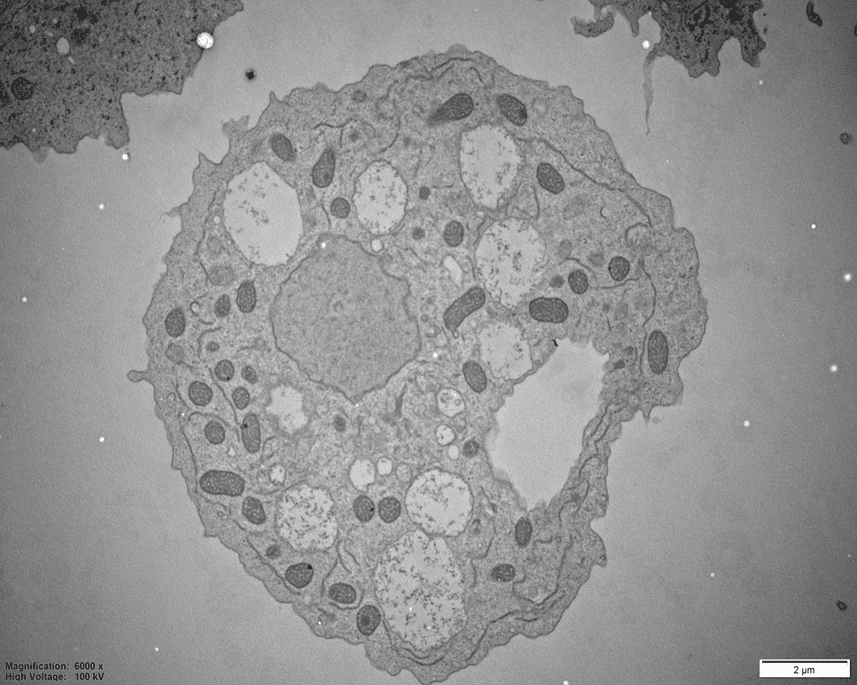

Acanthamoeba keratitis (AK) occurs when Acanthamoeba infects the cornea, leading to inflammation and damage to the cornea.

According to the current literature, infection is difficult to eradicate due to the absence of drugs that can kill Acanthamoeba in both its cyst and trophozoite life stages. This can lead to vision loss, with around one quarter of AK patients ending up with less than 25% of vision or becoming blind.

The researchers noted that while AK is very rare, estimated to affect 10-40 Australians per year, it is important, particularly for those who wear contact lenses, to be aware.

First author Mr Binod Rayamajhee, who is completing a PhD focused on Acanthamoeba at UNSW Medicine and Health, said Acanthamoeba from the environment can get trapped between the contact lens and the eye, leading to infection.

“Wearing contact lenses is the leading risk factor, particularly if people mix their contact lenses with contaminated water,” he said.

UNSW researchers previously found that around one third of the tap water in bathroom sinks in greater Sydney contains Acanthamoeba. Washing contact lenses in tap water is a major risk factor for AK, as well as showering and swimming with contact lenses in.

“There have been two previous studies, one in Sydney and another in Melbourne, suggesting that nearly 20% of patients acquired AK after swimming in seawater or fresh water with their contact lenses,” Rayamajhee said.

However, levels of Acanthamoeba in Australian aquatic environments have not been studied until now.

Testing NSW coastal waters

During the study, the researchers collected water samples from four NSW coastal sites. These locations are used for recreational activities such as swimming or kayaking, and water quality is monitored regularly for safety purposes.

Proximity of these sites to urbanised areas can lead to some water contamination, which potentially facilitates the growth of Acanthamoeba.

Co-author Professor Justin Seymour, who leads the Ocean Microbiology Group at UTS, said the sites were deliberately chosen.

“We chose coastal sites to look for the presence of Acanthamoeba species that we knew experienced high levels of seasonal variability in environmental conditions, as well as intermittent impacts from stormwater and sewage contamination. We aimed to identify any links between environmental factors and the presence of the organism,” she said.

The researchers collected multiple samples from each site each month from August 2019 to July 2020 (except March and April 2020 due to COVID-19 restrictions).

They measured water characteristics including temperature, dissolved oxygen concentration, pH, and salinity. In addition, the researchers extracted DNA from the water, which allowed them to measure the levels of Acanthamoeba and bacterial communities.

Acanthamoeba was present in water samples from all four coastal sites, with 38% of the water samples overall testing positive.

The prevalence of Acanthamoeba varied across the sites. For the most highly urbanised site, more than 50% of the samples tested positive. In contrast, for the least urbanised site, 32% of the samples contained Acanthamoeba.

The study found a positive correlation between the presence of Acanthamoeba and elevated levels of the intl1 gene in the water samples. The intl1 gene serves as an indicator of contamination in aquatic habitats due to human activity.

Taken together, these results suggest that urbanised coastal sites could be impacted by contaminants like sewage, animal faeces and stormwater, potentially creating a better environment for Acanthamoeba.

“The contaminated water allows the Acanthamoeba to flourish, as it feeds on the nutrients and a wide range of bacteria,” Rayamajhee said.

The researchers also found that Acanthamoeba was more prevalent in the water during the summer months. In January, 65% of the samples tested positive (the highest rate), compared to 5% in September (the lowest rate). They also found a weak positive correlation between water temperature and presence of Acanthamoeba.

“When we look at global data, there are more AK cases during summer, when recreational activities are likely to be at their highest,” Rayamajhee said.

“With rising temperatures and increased stormwater runoff due to climate change promoting algal blooms in seawater, urbanised coastal waterways could potentially become favourable habitats for Acanthamoeba. However, further investigation is crucial to accurately determine the prevalence of Acanthamoeba in the region.”

More reading

Daily disposables or reusables? One of these contact lenses increases AK infection risk three-fold

How much protein is deposited on RGP contact lenses?

The power of dual contact lens and glasses wear